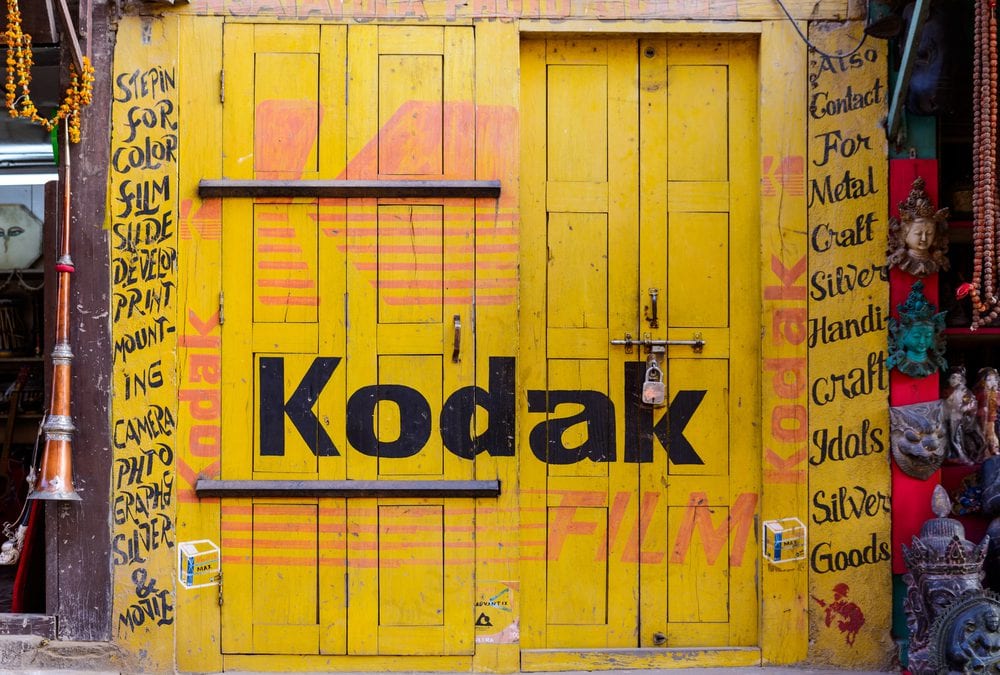

Remember how we used to buy memories?

We’d buy some film for our camera.

While we don’t buy film anymore, we still value memories.

In fact, we value and share memories more than ever – about 300 million photos uploaded every day. That growth wasn’t anticipated, especially by the world’s largest supplier in the film business – Kodak.

Despite being the largest supplier of film, despite creating the first prototype of a digital camera and despite buying a popular photo sharing site, KODAK mishandled the digital evolution, filing for bankruptcy protection in 2012.

How did they miss it? While a casual observer might dismiss the cause as film becoming obsolete, there are lots of deeper opinions. Check out here, and here, and here, if interested.

Anyway, I reckon it’s happening again.

This time in financial services.

RETAIL BANKS & KODAK

Just as the sale of film built Kodak, the sale of money products has built our retail banks, insurance groups, mortgage providers and finance companies.

Look no further than our compulsory superannuation to understand how the banks ‘sell us money’.

Realising the opportunities offered by superannuation, the banks devised expansion plans into ‘wealth management’ thus effectively selling us more products by offering superannuation funds. So, they began buying firms that understood this opportunity.

In 2000, NAB bought MLC from Lend Lease for $4.56B. In the same year, Commonwealth bought Colonial First State for $10B. Two years later, Westpac followed with a $900m purchase of BT. And in the same year ANZ started a joint venture with ING, eventually becoming a takeover.

Building upon their proven product models, the financial institutions undertook a giant buying spree consuming brands such as St. George, BankSA, Bank of Melbourne, Sealcorp, JBWere, Aussie Home Loans, BankWest, Mercantile Mutual, National Mutual. Their investors loved the returns as the retail banks consolidated their position dominating financial product distribution and cementing their place among the top end of Australian companies.

However, those efforts have now come undone.

Earlier this month the last of the four major Australian banks admitted the amalgamation of ‘wealth management’ into a banking institution was too hard and the ‘writing had been on the wall’ for a number of years.

Citing rising compliance costs, the constant regulatory inquiries surrounding advice client’s ‘best interests’, hefty compensation bills and associated brand damage, the retail banks are retreating to their strengths of product manufacture and distribution.

Makes sense.

Or does it?

Was the dalliance into advice by the retail banks a one-off, or a harbinger of the possible new norm for retail institutions distributing any financial product?

IT’S NOT ABOUT THE MONEY.

While Kodak’s advertising was brilliant proclaiming they were the brand for anyone who valued memories, their revenue flows, distribution and market domination were all dependent upon continued sales of film.

The film was but a ‘means’ to a much more valued ‘ends’ – the memories.

So too our banks and financial institutions.

The images and messages from the retail financial institutions marketing departments clearly understand what we value. Like Kodak’s situation, the product (e.g. superannuation fund) was but a ‘means’ to a much more valued ‘ends’, which for financial products is the impact or value their products uniquely provide.

As Kodak failed to build their expansion on the understanding that they were in the business of creating memories, our retail financial institutions are also perhaps failing to build their expansion on the understanding that they are in the business of making a valuable impact.

IT’S ABOUT IMPACT

Unless we get paid for the value we consistently and methodically create, there is a greater danger of suffering a fate similar to Kodak’s.

People like Steve Jobs love the opportunities created when the impact or value being promised is misaligned with payment methods. By focusing on what people value – creating memories – and aligning his product offerings and payments with a camera for everyone’s handbag or pocket (and with photo-sharing apps), Jobs better achieved what Kodak always aspired to.

Australians value the impact of having enough for their retirement, they value the impact of protecting those they love, they value the impact of buying a better home, they value the impact of building their small business.

For most of the retail banks’ customers, it’s not about the money but the impact the money provides.

To Kodak’s defense, any analysis is easy in hindsight.

It’s much harder to foresee a clear future path when there are no models of scale to compare to, when the technology is still untested, and when years of significant experience in product manufacturing and distribution have proven its value by creating a company whose products dominated the globe.

Giving away the ‘product’ and placing the price on the impact is a bold move in the compliance-focussed financial advice marketplace of today.

If you find yourself sitting in front of an adviser who says that their advice fee is not aligned to any product or hours worked, you may or may not be sitting in front of a Steve Jobs. But you are certainly sitting in front of someone on a brave and evolutionary path to align their advice purely on the impact it provides.

Bring it on.

What do you reckon?

About Jim Stackpool

For nearly 30 years Jim has influenced, coached, and consulted to advisory firms across Australia. As founder of Certainty Advice Group, he leads a like-minded team of professional advisory firms seeking to create greater certainty for their clients. As an author, blogger, columnist, and keynote speaker, Jim is regularly called upon for his professional insights into the advice industry. His latest book Seeking Certainty is available now.